.jpg)

Mongol Empire 1294 CE, at the death of Kublai Khan

Mongol Empire 1294 CE, at the death of Kublai Khan |

CONTENTS KEY

1. Introduction

2. Mongolian Tribes, Uighurs, the Jurchen, Tanguts, and the Song Dynasty

5. Conquest of Khwarazm and Khurasan

6. Mongol Generals and Christian Crusaders

7. Farid al-Din Attar, the Nafs Scenario, and Yazidis

8. Hulagu, the Siege of Baghdad, and Mamluks

11. The Golden Horde and Later Eras

13. Kublai Khan, Emperor of China

14. Mongol Conversion to Buddhism

15. Soviet and Mongolian Communist Savagery

16. Chinese Communist Oppression of Tibet

18. Self-Immolation of Tibetan Protesters

19. Muslim Uighurs and Falun Gong

The Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century are currently a popular topic, stimulated by cinema, and covered in diverse internet formats, including recreation games. Toy soldiers are a commercial byproduct. You Tube conveys excitement (and some documentary). Many internet features and blogs do not cite a single book. Military histories offer portrayal frequently loaded in favour of strategy at the expense of other details. The Mongols serving Genghis (Chingiz) Khan definitely were a military phenomenon. There are different ways of confronting the records. Slaughter is not an attractive occurrence. There is nothing wonderful about being hacked to death by a sword or having the skull crushed by an axe. The number of new recruits at that era for the international slave trade is unknown, but was evidently high.

When a Mongol leader stipulated no quarter, the consequence for inhabitants of towns and cities was horrific. Warriors are very popular in the Western "new age" of spirituality lore and magic; the cinema and video vista varies from samurai to fashionable muscular barbarians starring in nonsense plots. Some real life strategies of Mongol warriors did not arouse enthusiasm amongst invaded peoples during the medieval era. The same can be said of Timur and other warlords.

|

Movie portrayals frequently arouse scepticism. The question of accuracy is prominent in discussions. An early instance was The Mongols (1961), featuring Jack Palance as Ogedai (son of Genghis), with the consuming desire to conquer Poland. This was not Hollywood, but a less ambitious European production, nevertheless falling short of historical authenticity. Even the hairstyle was wrong.

The more recent Mongol (2007) satisfied general audiences but not historians. Sceptical movie reviewers found parts of this colourful Sergei Bodrov epic more reminiscent of pulp fiction than the reality. The film invited critical comparisons with the 1982 Arnold Schwarzenegger Conan the Barbarian. A punchline in Mongol was highlighted: "All Mongols do is kill and steal." Another word found in critical appraisal is fantasy. There is no commercial demand for history, a situation singularly convenient to entertainment vogue.

|

Mongol is described by Wikipedia as a "semi-historical epic film." Many American movie reviewers were enthusiastic, recognising that the Asian cast was a substantial improvement upon John Wayne and related improvisations of yesteryear. However, these reviewers were not historians. In contrast, Mongolian reception was sober, detecting factual errors and anomalies. A strong complaint of Western critics is that Mongol glorifies Genghis as a hero. This figure caused a staggering number of international deaths and razed numerous cities to the ground.

Concerning book coverage, an expert in this field reported: “One popularisation [of the Mongols], based on a doubtful and distorted use of scholarly studies, even reached the best-seller lists and influenced serious books on current foreign policy” (Rossabi 2009:xi).

One of the incontestable facts is:

In the mid-thirteenth century, the ‘Great Mongol State’ (yeke mongghol ulus) was the largest contiguous land empire in the history of mankind. It controlled an expanse of territory stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean and ruled over a multitude of peoples and states differing widely in language. (Allsen 1983:243)

Former European commentators were often severe in their judgment of the Mongol Empire, which created a high death toll. More recently, the Western coverage moved into glamorising versions of what happened, creating an overlay of cosmetic literary flourishes and commercial cliche.

In the past two decades, however, popular writers, using this and other books, started to portray the Mongols in heroic terms, approaching a hagiography of Mongol leaders such as Chinggis Khan and Khubilai. They depicted Chinggis Khan as the harbinger of the modern world in his attitudes and policies and as a symbol of democracy because of his alleged consultation with the nobility on important decisions and his support of women’s rights…. They tended to ignore the darker and more brutal side of the Mongol invasions. This distorted image of the Mongol Empire, unfortunately, appears to be gaining greater popular acceptance. (Rossabi 2009:xiii-xiv)

A very disconcerting feature of Mongol Empire mentality was the attitude to resistance. The violence attending invasions was extreme. Partisans of the Mongol Empire tend to justify drawbacks by invoking more positive features resulting from that regime, for instance, economic growth. Whether economic benefits outweigh slaughter is debateable. A basic factor emerges:

In their [Mongol] view, all peoples and nations were potential members of the Mongol-empire-in-the-making, and everyone, after being duly informed of the requirement, was obliged to submit to the Mongol khagan (supreme ruler). Those who failed to do so were considered rebels and treated accordingly. In Mongol terms this usually meant the destruction of the offending state and the partial annihilation and enslavement of its subjects. (Allsen 1983:268)

In more general terms of shamanistic warrior societies of Inner Asia, beliefs can sound very crude. Realism is preferable to romanticism. “Warriors have believed that the massacres committed by them were due to Heaven’s ‘making pressure,’ and that the enemies whom they killed would be transformed into slaves to serve them in the next world” (Baldick 2000:3).

Genghis Khan and his successors assumed the status of “a supreme, heavenly mandated ruler, the Qaghan (later Qa’an, Khan ‘emperor’), a title of unknown origin used by Turkic and Mongolic peoples” (Cosmo 2009:1). The overwhelming legitimation for this status was military. Other dimensions of the Empire situation are expressed as follows:

Their major and minor courts across the different Mongol states remained remarkably open to multiple cultural influences, and the circulation of ideas, technologies, material goods, religions, and even food and entertainments benefited from the eclectic taste and multi-cultural environment that Mongol leaders generally favoured. The Mongols, of course, made choices as to what they accepted and what they rejected, a matter that was made painfully clear to Christian missionaries who attempted to convert Mongols but were far less successful than Buddhist monks and Muslim mullahs. (Cosmo 2009:3)

2. Mongolian Tribes, Uighurs, the Jurchen, Tanguts, and the Song Dynasty

Depiction of Genghis Khan |

Temujin, alias Genghis Khan (1162-1227), was an ambitious shamanist who believed he had a mandate from Heaven (Tengri) to conquer other countries. He was a killer from the age of 13. Life in freezing Mongolia was harsh, made worse by savage rivalries between tribes. Enemies could be boiled alive. Genghis hated the Tatar tribe who killed his father; he had every male member of that clan killed.

The Mongolian Plateau was inhabited by tribes such as the Naimans, Merkits, Tatars, and Keraits. Raids for horses and women were frequent activities, with revenge attacks another complication. Some rivals supported the Mongolian aristocracy, while Genghis attracted a broader range of followers, making attempts at integration of defeated tribes. He was nevertheless ruthless, being prepared to decapitate civilian prisoners in the struggle with rivals.

The anonymous and partisan Secret History of the Mongols details the ancestry and life of Genghis. This is the oldest surviving literary work in Mongolian, covering the reign of Genghis and his son Ogedei (Rachewiltz 2004-13). Sources in other languages are a relevant complement. Ascertaining facts is not always straightforward. The myth of Genghis Khan requires a flexible approach. Modern analysts say that Genghis fathered a thousand or more children, a detail which not everyone views with admiration.

In 1206, Genghis (Chingis) Khan united the strife-torn nomadic tribes of Mongolia (about half of that population were Turkic-speaking people). The precarious nomadic existence of Mongolian tribes was transformed into a formidable military force, exacting tribute and gaining wealth through looting. A major target was soon to be China.

Strained relations between Inner Asian nomads and the Chinese were a recurring development, going back to the first millennium BC, when the nomadic Hsiung-nu were enemies of the Han Chinese (Cosmo 2002; see review). One explanation reads: “When the Chinese refused to trade, they [the steppe nomads] organised raids to obtain by plunder the goods they could not secure through peaceful means” (Rossabi 2009:3). However, in the case of Genghis Khan, the ambition of conquest was evidently the foremost consideration.

The shamanistic character of Mongol society was pronounced. Components of this shamanism were ancestor worship, divination, and communication with “spirits” by shamans (called boes or idugens). Major deities revered were Tengri (the “sky god” or “everlasting Heaven”) and the earth goddess Itugen. Shamans were credited with the ability to interpret the “Will of Heaven.” The dominant belief of Genghis Khan, that he had a mission to conquer the world, may have originated from a shaman.

At the quriltai (great gathering) in 1206, the shaman Kokchu was a participant. His presumed magical powers caused him to be held in awe. “He was reported to be in the habit of ascending to heaven on a dapple-gray horse and conversing with spirits” (Grousset 1970:217). Kokchu attempted to exploit his prestige by interfering with the royal family, turning against brothers of Genghis. With the “tacit consent” of Genghis, three soldiers murdered Kokchu by breaking his spine, his death occurring without blood as preferred by etiquette (ibid:218). The shamanist powers had lost to brute force. Genghis appointed another shaman for the royal house.

To the south, in East Turkestan, the Buddhist Uighurs of Qocho submitted to Mongol rule in 1209, with the consequence that their cities were left untouched by Genghis Khan. The Uighurs were a Turkic people originating in Mongolia. They were the most literate population amongst the Turks (who included Kipchaks), and more civilised than the Mongols. Genghis recruited these people into government service. They served widely as government officials, secretaries, translators, and teachers. The Uighurs adapted their own vertical script, in this way producing the first written Mongol language (Rossabi 2014:423-424).

The Uighurs established themselves as a refined military class defending Buddhism. One of the two principal groups of Uighur moved into the Tarim Basin during the ninth century CE, developing there a sophisticated culture replacing the earlier Uighur shamanist model. This development was facilitated by permanent settlements and Buddhist temples. The new Uighur state was based on oasis settlements rather than grazing zones (Samolin 1964:72ff).

Jin Dynasty fresco of a Buddhist Bodhisattva, Chongfu Temple, Shuozhou, Shanxi Province |

A very resistant foe were the Jurchen Jin, shamanic agriculturalists. Originally a semi-nomadic people of Manchuria, they infiltrated North China, rebelling against the Khitans who had established the Liao Empire. From 1127 they controlled North China, to some extent assimilating Mahayana Buddhism, a religion which tended to sublimate their martial edge. The Jurchen people spoke a Tungusic language; they were ancestors of the Manchus. The Jurchen Empire fought the Chinese Song dynasty, who withdrew southwards, lacking the same military strength. Chinese sources report that the Jurchen had many shamans, both men and women, who would sacrifice pigs or dogs when treating illnesses. In one of these rituals, a white dog was impaled on a pole (Baldick 2000:10). Realistic practices of shamanism have been obscured in popular literature of the Western new age.

In 1153, the Jurchen made Zhongdu (Beijing) their capital. Two generations later, this city was besieged by Genghis Khan, whom the Jurchen regarded as a barbarian. In 1210, envoys to Mongolia from Zhongdu announced the accession of their new Golden Khan, demanding acceptance of this ruler. Genghis refused, instead invading Jurchen lands. In 1211 the Mongols assaulted the Great Wall of China, with thousands of casualties on both sides. The Jurchen army were soon defeated, their corpses stretching over a distance of thirty miles. Genghis now split his army into three, for the purpose of striking many cities throughout North China. They are reported to have murdered and raped the inhabitants of ninety cities, which suffered the additional calamity of looting and burning.

By now, the Mongols had captured over a 100,000 Chinese prisoners. With a total lack of mercy, Genghis Khan had these people executed. This was a terror tactic designed to support his new plan of negotation with the Jurchen, whom he wanted to pay tribute in return for no further molestation. The Jurchen Emperor moved his court from endangered Zhongdu south to to the city of Kaifeng, where the army was reinforced. Genghis was annoyed at what he considered a betrayal. The Jurchen army were again destroyed.

There followed the siege of Zhongdu in 1215. This large city reputedly harboured a million inhabitants; the figure is tapered to about 350,000 by some modern scholars. Hapless Jurchen prisoners were used as human shields while pushing siege engines to the city walls. Many of these people were killed by crossbow fire intended for Mongols. The siege continued for a year, with starvation and disease resulting on both sides. The desperate inhabitants opened the gates, begging for mercy. The Mongols looted, raped, and massacred. The city was set on fire. Thousands of young women ran in terror to the steep city walls, jumping to their death, fleeing from the flames and invading rapists. No Hollywood scenario could adequately depict the horror of realistic events.

Years later, in 1231, the Mongol general Subutai made a last determined effort to conquer the resistant Jurchen, who now gathered a large army of 300,000 men. The cunning Subutai trapped them in the mountains of Sichuan, where freezing conditions killed many. The Mongols captured the enemy baggage train, causing starvation. The victims were allowed to escape this situation, only to be ambushed on the plain, being massacred within sight of Kaifeng. That city traditionally numbered a million people. The Chinese Song army, from the south, had become allies of the Mongols. This powerful combined force assaulted the walls of Kaifeng, being repulsed by incendiaries that left craters in the ground. Plague appeared in the city, causing havoc. The bloodthirsty Subutai commenced his strategy of massacre; he had been doing this for many years. He wanted to make the agricultural land into grazing fields for horses.

A Khitan adviser exhorted Ogedei Khan (son and successor of Genghis) to prevent massacre, arguing that the city population could provide a useful source of taxes, craftsmen, and soldiers. The persuasion succeeded. Subutai was ordered to avoid slaughter. However, in 1234, the Jurchen Empire suffered termination after further struggle with Song and Mongol forces.

Tangut warriors (Western Xia) |

Genghis Khan also relentlessly attacked the Tangut Empire (1038-1227) in north-west China. He reputedly expressed a wish, while on his deathbed, for the Tanguts to be eliminated. This shamanist resolve is not attractive. A modern complaint is that Genghis attempted genocide (Man 2004). The Tanguts had been in strong resistance to his invasions over the years. After the first attack in 1209, the Tanguts had become tribute payers, their subsequent rebellions being brutally squashed. In 1227, the Mongols terminated the Tangut Empire, destroying the Tangut capital of Yinchuan, ruthlessly killing many thousands of civilians, and also the last Tangut Emperor. They destroyed the manuscripts of a far more literate people.

A substantial hoard of related ancient documents was found by Sir Marc Aurel Stein at the Dunhuang oasis in 1907. The well known Mogao Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, dating back to the fourth century, honeycomb the face of a cliff at this old site on the Silk Road in Gansu province. Stein found that the collection was guarded by an unlettered Taoist priest, who was persuaded to open a secret chamber where manuscript bundles rose to a height of nearly ten feet, the volume close on 500 cubic feet. Most of these texts were Buddhist, written in Chinese, covering a period of six centuries. The scroll documents were apparently collected together for safety from local monasteries. Much of the content is in a popular idiom, though including fairly detailed notices of eminent Buddhist monks (Giles 1944:5, 7ff). The Tanguts captured Dunhuang in 1036, the town being destroyed by the Mongols in 1227 (later rebuilt).

The Tanguts are known as the Western Xia, or Xi Xia (also Mi-nyak). They came from Tibet, speaking a Sino-Tibetan language. They are described as a federation of tribes related to the Tibetans. Tanguts were famed as riders, being prominent in the horse trade. They absorbed some Chinese influences. Nevertheless, Buddhism became their state religion. In Tangut society, women could become influential nuns.

The Mongol and Song Empires were subsequently in friction. In 1235, the Song tried to occupy the Jurchen cities, which they now believed to be their property in return for assisting the Mongol invaders. They met with frustration; the Mongols repulsed them. By 1248, the Mongol warriors had killed "hundreds of thousands" of Song people, to quote one version. In the province of Sichuan, they left many cities in ruins. Everywhere they went, the same destruction occurred. The war with the Song Empire continued for many years, ending in a Mongol victory. The very substantial Song capital city of Hangzhou was burned in 1275 by the army of Kublai Khan. Another massacre here occurred. The Mongol army had now killed up to 25 million people in China via war, plague, and famine (How the Mongols Made the World Tremble).

Han Chinese lady in traditional robe |

The Song dynasty, famous for Chinese art and culture, is identified with the Han Chinese population, comprising one of the oldest civilisations. The Song era is also noted for the more notorious custom of binding female feet, favoured by the higher classes. Han Chinese princesses were terrified at the prospect of rape from invaders, even while their own men imposed an extremist fashion. The damaged feet were constricted to a length of four inches.

Footbinding later spread to other social classes during the Manchu (Ching) era. Many low class women had to work long hours with this affliction, which was officially banned in 1911. Footbinding is associated with Confucianism, an urban patriarchal tradition presiding over a clear preference for sons instead of daughters (Attane 2013).

Bound feet were out of the question for the vigorous women of the Mongolian steppes. Mongol women could become shamans and archers. However, they did not achieve true equality. In theory, Mongol women were permitted their own property; nevertheless, men generally inherited wealth in the patrilineal system of descent featuring in Mongol society (Rossabi 1979:154).

Depiction of Mongol Cavalry |

In 1204, Genghis Khan created the keshik (bodyguard), consisting of a few hundred men. In 1206, this elite body reputedly expanded to include 10,000 men. The keshik provided intensive military training, military commanders, and civil administrators. “One key difference between the Mongols and their opponents was the consistency of command among the Mongols” (May 2017,1:80). Genghis Khan imposed upon his army rigid rules demanding obedience, with severe punishments being exacted for lapses. Flogging was a mild penalty. Desertion of duty could result in speedy execution. If one man retreated from his unit of ten, the other nine were also put to death. See further Mongol Warfare and Military Tactics.

The Mongols were very disciplined fighters with stamina, while resorting to tactics that could easily deceive opponents. They favoured surprise attack and feigned retreat transpiring to be a lethal trap. They were masters of the horse, being trained to ride from the age of three. Their horses were small, not the fastest breed, but strong and resilient. The Venetian traveller Marco Polo (1254-1324) records the Mongol habit of remaining on horseback for two days and nights, without dismounting, sleeping in the saddle while the horses grazed. Other nations could not match this equestrian facility. Mongol warriors could travel up to seventy miles a day (and more).

In shamanic ritualism, horses were sacrificed with their owner. At least forty horses were reputedly sacrificed at the tomb of Genghis Khan. A Mongol belief was that these dead horses could take the owner to Heaven, where he could continue riding.

.jpg) |

Mongols were adept with the bow and arrow, being able to shoot proficiently while mounted at full gallop. They could shoot arrows over 350 yards (M. Rossabi, "All the Khan's Horses," 1994). This was because the composite Mongol bow (made of wood, horn, and sinew) had a strong draw more powerful than the English longbow (achieving 250 yards). The tension of the Mongol bow required two men to string this serious weapon.

Spears, knives, swords, and axes were also basic equipment. The Mongol sword has been described as a slightly curved scimitar. Some historians believe that the notorious massacres were achieved by slitting the throat, a relatively speedy process. The current cinema and video vogue for Mongol conquest is dramatically visual, but would be less likely to appeal if all the realistic details were conveyed.

The Mongol army was accompanied by extensive herds, including the essential spare horses used for remounts. The soldiers shaved their hair short on the top and back of the head, leaving hair long on the sides, often in braids. They wore light armour made of leather or felt. They were not keen to bathe and never washed clothes. The nomadic lack of hygiene is often criticised today. The Mongol women cooked meals and repaired clothing, but washing clothes was not a recognised duty. “The Mongols believed that the washing and drying of clothes enraged the gods” (Rossabi 2014:327-328). A modern explanation is that Mongols did not wish to waste their precious water supply.

The Mongol army conscripted many men from allies and conquered territories. Uyghurs notably featured in this complement. These extras eventually came to outnumber the Mongols. In the Golden Horde Khanate, the majority of warriors were Kipchaks, a Turkic race (associated with the Cumans, who were frequently their close neighbours). Obscured tribal history is the subject of rigorous scholarly analysis. Ethnic complexities of the Mongol Empire still await final resolution.

Early descriptions convey that Mongol men were generally of medium height, with lean waists, facilitating their equestrian lifestyle. Urban obesity was not regarded as a virtue. However, a deterioration occurred during the Empire phase. Mongols were partial to the fermented horse milk called airag (or kumis), of low alcoholic content, which they consumed in quantity. This indulgence gained notoriety. "Some of the Mongol Khans and members of the elite consumed vast quantities of liquor, including airag" (Mare's Milk). The Empire gave access to wine. Too many Mongol rulers drank themselves to death; short reigns became common. Royal women shared the indulgence, which together with a heavy diet, caused obesity (J. Masson Smith Jr, "Dietary Decadence and Dynastic Decline in the Mongol Empire," 2000).

According to Marco Polo, the Mongol army mobilised between 600 thousand and 650 thousand men in an activity extending to the Middle East and Russia. Modern scholars have frequently tended to dismiss such estimates as fantastic exaggeration. There are nevertheless differences of opinion. A Russian commentator referred to the situation in terms of "a hundred thousand conquering a hundred million." Russia and China are here under discussion. During the twelfth century, the population of China may have been one hundred million. Even today, the Mongol population is only some three million. However, the Mongols gained substantial reinforcements. By the 1240s, the sprawling Mongol Empire included the entire Inner Asian steppe, including the very numerous nomads and mounted archers in that zone. The "Mongol" army not only comprised Mongolians, but also diverse Turks, Tibetans, and Tungusic peoples. To some extent, this army also incorporated Georgians, Russians, and Chinese, to name only a few of the non-nomadic participants (Masson Smith Jr, 1975:272-273).

Mongol woman in traditional costume |

"Women played critical roles both in Chingis Khan's life and in the development of the Mongol Empire" (Broadbridge 2018:1). This scenario includes the new Emperor's mother Hoelun and conquered women from other communities (see also De Nicola 2017 for extensions in Iran).

Women managed the nomad camps with their inhabitants, gear, and flocks; the biannual migrations between summer and winter camping sites; and irregular travelling camp movement during military campaigns. (Broadbridge 2018:2)

Marco Polo reported that Mongol women did all the work, while the men were committed to hunting, hawking, and war (Rossabi 2014:327). The women tended the herds and flocks while the men were away hunting; those herds comprised horses, sheep, goats, and cattle (also camels). We know that the men made arrows, while the women made all felt and leather items. Women had the crucial task of setting up the camps of yurts (tents), and also packing up the tents. They drove the essential carts for transport. In nomad society, women shared male athletic pursuits, even wrestling. Many women were expert riders and archers. In a minority of instances, women joined the fighting. A daughter of Genghis Khan led a detachment in the final assault on Nishapur (ibid:328).

At the imperial level, "senior wives ran camps with the assistance of servants and staff" (Broadbridge 2018:2). As the Mongol Empire expanded, the staff increased to thousands. These camps of yurts (tents) were mobile cities, in which women were dominant. Women regularly engaged in trade. During war, they gained portions of the plunder. Large numbers of slaves were transported to the royal camps or tent towns, which became centres of mercantile activity. The Turkic term ordo referred to a camp or court.

In the Mongol Empire of the thirteenth century, some women acquired substantial political influence. Sorqoqtani Beki (d.1252) was reputed to be the most exceptional woman of her time. Chinese historians praised her intelligence and generosity. She was the niece of Ong Khan (Toghrul), an early ally of Genghis Khan. She came from the Kerait tribe, a Turkic community who converted to Nestorian Christianity in the twelfth century. She was married to Tolui (d.1232), a tough fighting man addicted to alcohol. When Tolui died prematurely, Sorqoqtani declined further offers of marriage, remaining a widow. She recognised that the Mongol warrior tendency to exploit Chinese peasants was a disastrous policy (involving much plunder). She employed Chinese advisers in her administration, and favoured the native agrarian economy instead of a Mongol pastoral regime. She thus identified with sedentary civilisation, preferring Chinese tutors for her sons Mongke (d.1259), Arigh-Boke (d.1266), Hulagu (d.1265), and Kublai (d.1294). These offspring were nevertheless trained in the traditional Mongol warrior lifestyle.

Despite her Nestorian background, Sorqoqtani did not discriminate against other religions. She patronised both Buddhism and Taoism, while the Persian historians praise her benefactions to Islam. She gave alms to poor Muslims and funded mosques and madrasas (including the Khaniya madrasa in Bukhara). She employed Muslim artisans and merchants from Central Asia and Persia.

Her son Mongke was married to a Nestorian, though he remained a shamanist in outlook. Hulagu likewise married a Nestorian, a factor which made him sympathetic to that religion. The principal wife of Kublai Khan was Chabi, a Buddhist who influenced official government policy (section 13 below). After the death of Sorqoqtani, her sons became more aggressive. Both Kublai and Hulagu briefly discriminated against Muslims in China and Persia respectively. Kublai and Arigh-Boke were locked in a struggle for power during 1260-64 (Rossabi 1979:158ff).

Women could also be ruthless in their strategies. Sorqoqtani and her son Mongke instigated the trial of their female rival Oghul Qaimish Khatun (d.1251), a Merkit who was regent of the Empire after the death of her husband Guyuk Khan (d.1248). The rival was accused of witchcraft. This victim was stripped naked, tortured, and drowned, being bound in felt so that she could not escape. "Such accusations [of witchcraft] provided a convenient mechanism for disposing of unpopular rivals" (D. Hamil, "Oghul Qaimish Khatun," in May 2017,1:170). The death of this alleged witch benefited Mongke, who became the next ruler of the Mongol Empire. The various royal frictions and rivalries are noted for dividing the Empire created by Genghis.

Meanwhile, Toregene (rgd 1241-46) acted as regent for her son Guyuk, a grandson of Genghis. Toregene was the wife of the Great Khan Ogodei (rgd 1229-41). Toregene increased taxes in her East Asian territories, opposing a minister who adopted the opposite policy of reducing tax. Toregene was here furthering a nomadic tactic, contrasting with her more benevolent rival Sorqoqtani (Rossabi 1979:163-164). The heavy taxation appears to have encouraged corruption amongst tax collectors, who afflicted farmers.

5. Conquest of Khwarazm and Khurasan

The Arab phase of Islamic Khurasan was a memory by the time the Saljuq Turks took control in the 1040s, resulting in the Khwarazmshah rule, meaning Saljuq vassals who became independent. Persian officials were employed in the bureaucracy. The Khwarazmshahs (or Sultans) eventually rivalled the Abbasid caliph, their empire extending to West Iran during the 1190s. The campaign in West Iran continued until 1217-18, just before the Mongols appeared in Khwarazm (a part of Greater Khurasan). Khwarazm was an ancient Iranian territory south of the Aral Sea, eastward from what became generally known as Khurasan.

The Turkic Sultans created close links with the Oghuz Turkmen and Kipchak tribes to the north of Khwarazm. “Many of these Turkmens were still pagan, and they gained notoriety in Persia for their barbarous violence and cruelty” (C. E. Bosworth, “Khwarazmshahs,” Encyclopaedia Iranica). The Oghuz (or Ghuzz) sacked Nishapur in 1153. Large numbers of Kipchak tribesmen were recruited into the Khwarazm army during the late twelfth century.

The Khwarazmshah Ala ad-Din Muhammad II (rgd 1200-1220) lived in an opulent world of palaces, harems, slaves, and violent soldiers. His army was large, reputedly 400,000, reassessed today at much lower figures (varying from 60,000 to 170,000). “Khwarazm was a familiar blend of a Turkic military elite ruling an Iranian agrarian and urban population that was already undergoing Turkicisation” (Golden 2009:14). In 1212, the city of Samarkand rebelled, killing thousands of Khwarezmians amongst the population. The Shah retaliated by sacking the city and executing ten thousand inhabitants. He subsequently marched on Baghdad, intending to depose the Abbasid Caliph. The incursion was frustrated by severe weather conditions that decimated his army.

Genghis Khan wanted to expand trade with other countries. In 1218, he sent a large caravan of merchants to Otrar, a city in Khwarazm. The governor Inalchuq, a relative of Shah Muhammad II, murdered the entire caravan of over 400 people, considering them to be spies. This was a convenient excuse to acquire the caravan merchandise. Genghis then sent three emissaries, one of them a Muslim, demanding reparation. The Shah executed the Muslim envoy and sent back the two Mongol envoys to Genghis after burning their beards. This aggressive response was deemed an outrageous insult. The consequence was a dire programme of retaliation.

Reconstruction of Mongol cavalry warrior. Courtesy The Art Science Museum, Singapore |

Genghis Khan invaded Khwarazm in 1219, an operation lasting for two years. Genghis divided up his army, sending the warriors in different directions. The Shah soon fled from the dramatic reverses he suffered. His 21-year old son (Jalaluddin Mengubirni) moved south, gaining support in Afghanistan against the enemy.

Historians differ about the interpretation of some events. The Persian chronicler Juvaini (1226-1283) wrote History of the World Conquerer, an important record of Mongol activities. This and other sources feature some exaggerated death tolls, created through hindsight. Inflated numbers become understandable in view of a shock factor. “The death and destruction was on a scale quite beyond contemporaries’ previous knowledge or experience” (D. O. Morgan, “Cengiz Khan,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

The Mongol invasion of Khwarazm and Khurasan is notorious for destruction. The Islamic cities of Balkh, Merv, Nishapur, plus other urban sites, were annihilated. The Mongol army are estimated to have killed between two and four million civilians in this zone (the overall total of casualties, achieved by Mongol aggression from China to Europe, is assessed at 30 million or more).

Otrar was the first Khwarazmian city to be smashed by Genghis. The inhabitants were killed or enslaved after a siege; the offending governor Inalchuq was executed. The Mongol army then moved south across the Kizyl Kum desert, generally considered impassable. The Mongol cavalry were accompanied at the rear by a large herd of spare mounts. They arrived at Bukhara in 1220. The garrison defenders went out to fight, only to be massacred. Genghis allowed his soldiers to plunder. “All the inhabitants were driven out, their property pillaged, and the city burned; the defenders of the citadel were slaughtered” (Y. Bregel, “Bukhara iii. After the Mongol Invasion,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

According to Juvaini, one Turkic group at Bukhara met with severity. “No male was spared who stood higher than the butt of a whip and more than thirty thousand were counted amongst the slain” (Rossabi 2014:424). Genghis is said to have declared: “I am the punishment of God [Tengri]” (Lane 2004:xxxvi). The shamanists from Heaven were certainly ruthless and cruel with their weapons.

One view is that the invaders may have unintentionally set fire to the almost exclusively wooden structures of Bukhara, turning much of the city to ashes. Some of the populace were enslaved, others apparently enlisted into local armies raised to support the Mongol invasion. Neighbouring cities quickly fell to Mongol control, "in most cases more or less intact" (Buell 1979:129ff). The resulting forty years of Mongol rule saw these cities rise again to prominence; the details are sparse (ibid:121). Regaining prosperity, Bukhara is depicted as a centre of Sufism featuring the Kubravi shaikh Saifuddin Bukharzi (d.1261), a figure often credited with the conversion of Berke Khan to Islam (DeWeese 1994:83-87).

Depiction of a Mongol army officer |

A notorious Mongol tactic was to use civilians as human shields, including women and children. The prisoners were dressed as Mongol soldiers in an attempt to draw and exhaust arrow fire. This strategy occurred during the attack on Samarkand, the capital of Khwarazm, in March 1220. This city was much bigger than Bukhara, and better fortified. Thousands of helpless people were reputedly involved in the “trick” strategy. Moreover, half the garrison of 40,000 were lured out of the city by an elaborately feigned retreat. The jubilant optimists were slaughtered by formidable warriors wielding swords and axes.

The 100,000 inhabitants of Samarkand suffered a further massacre. However, different versions of this event can be found. A traditional report says that 30,000 artisans and engineers were taken captive for the journey north (Rossabi 2009:7). Genghis certainly looted the city. The Mongol leader used large catapults and other siege engines in his strategy; for this recourse, he needed Chinese experts and Muslim engineers.

Genghis despatched three of his sons north to Gurganj, a wealthy Silk Road trading city on the northern edge of the Kara Kum desert. This site, also known as Urgench (now in Turkmenistan), had existed since the Achaemenian era. The Mongol force is estimated at 50,000. The siege encountered a strong defence, resulting in substantial Mongol losses. The final outcome was a slaughter of inhabitants, the women and children being enslaved.

Meanwhile, Shah Muhammad II was chased through Iran by the Mongol generals Jebe and Subutai. In 1220, the Shah died on an island in the Caspian Sea, his position one of complete defeat. He was reputedly buried in the rags of a servant. He certainly knew by then that his gesture of political contempt had precipitated hell on earth for his subjects. His grim and marauding pursuers moved on into the Caucasus with at least 20,000 men, smashing resistance everywhere they went.

In another direction, Genghis Khan’s son Tolui was despatched to attack cities in Khurasan, here meaning the westernmost territory of Central Asia. At Balkh, the city governors were not prepared to fight, instead surrendering while making many gifts. The Shah’s son Jalaluddin Mengubirni (rgd 1220-31) was an active rebel in exile, the reason given by Juvaini for a dire Mongol order that the inhabitants “should be driven out on to the plain and divided up according to the usual custom into hundreds and thousands to be put to the sword” (Boyle 1997:131).

A complexity is discernible in two Mongol visits to Balkh, leading to different interpretations. The first one, in 1220, was apparently mild because of the surrender. The following year, Genghis returned from Peshawar to Balkh, with a severe outcome. A revolt against the Mongol garrison may have been the reason for massacre. “He [Genghis] commanded them all to be killed” (ibid). Juvaini cites the Quran as an anticipation of this development: “Twice will we chastise them” (Quran 9:102). The Mongols destroyed the city walls. When a Taoist monk from China passed what remained of Balkh a year later, “he reported that not a soul remained” (Starr 2013:447). The city was in ruins for more than a century.

Depiction of Shah Jalaluddin Mengubirni |

A major event was the rallying action of Shah Jalaluddin Mengubirni at the battle of Parwan, about fifty miles north of Kabul. The Afghan location was a narrow valley unsuited to cavalry. The battle was to some extent an archery contest. For the first time Mongol tactics faltered into retreat. The new Khwarazmshah was victorious, killing half the enemy. This event caused a sensation, influencing northern cities to revolt against Genghis, a trend discernible in the sources. However, Mengubirni was obliged to retreat south, subsequently losing a battle at the Indus River in 1221, during the first Mongol invasion of India. The Mongols plundered Multan, but then turned back, defeated only by the Indian heat.

Mengubirni only narrowly escaped the Indus battle. He drowned his women in the river to assist his desperate solitary charge through Mongol ranks. The Mongols then killed all his family and followers. The fate of women in these warrior societies was deplorable. Only the sword and axe counted. Monarchical prestige and victory was paramount.

Meanwhile, at Merv, a large population were protected by walls fifteen feet thick and thirty feet high. The governor surrendered after a struggle. Tolui Khan had promised that civilians would be spared. Nevertheless, he now ordered most of the people to be killed. This would mean about 100,000 or more inhabitants. The exceptions were 400 artisans and some children, who now became slaves. According to Juvaini, each soldier was allocated the execution of three or four hundred people (Boyle 1997:162). About 5,000 civilians somehow survived the plunder and massacre. However, a rearguard body of the Mongol army killed most of these survivors, while also killing refugees fleeing on the road to Nishapur (ibid:162-163). The punitive rearguard tactic was a nasty feature of Mongol warfare.

One reason for the unrelenting severity at Merv was the death in battle of Tokuchar, a son-in-law of Genghis. The widow of Tokuchar is reported to have figured prominently in the massacre. The heads of the corpses were severed and heaped in piles. One pile for the male heads, the other for the women and children. This was evidently intended as another terrorist gesture for public edification. When Tolui moved on to Herat, he left 400 men to kill any survivors they might find. The city of Merv was destroyed, the buildings “levelled with the dust” (ibid:178). Islam had achieved an advanced literary culture. Merv could boast ten libraries, reputedly holding 150,000 books. The illiterate Mongols cared nothing for books, which were totally dispensable items in their programme.

The warlord Tolui besieged Herat and annihilated the entire garrison (reportedly 12,000 men). However, he spared civilians. When the army departed, the inhabitants of Herat killed the Mongol deputies. The invaders returned in 1221-22, mounting a six month siege. The city was afterwards totally destroyed and the entire population massacred. The Mongol leaders sent “search parties throughout the countryside to exterminate any possible survivor” (M. Szuppe, “Herat iii,” Encyclopaedia Iranica). Herat did not recover until the fifteenth century.

Tolui moved on to Nishapur with a large force (of uncertain number). The inhabitants here had lost hope after a harsh winter. They sent their chief qazi (legist) to Tolui, requesting mercy, and agreeing to pay tribute. The cleric was not allowed to return. Instead, the Mongols scaled the city walls and fought on the ramparts. When the victors descended into the city, they killed and plundered, the survivors afterwards being driven out on to the plain. Tolui gave the command that Merv should be destroyed. All survivors were killed, except for craftsmen who were enlisted into the Mongol war machine. “The crafts concerned with the manufacture of weapons were of special interest to the Mongols” (Lambton 1988:344).

Persian painting of Tolui Khan, early fourteenth century |

Years later in 1232, Tolui drank himself to death (Rossabi 2009:12), a fate by no means unique amongst the Mongol elite. The source for this version is Juvaini. Tolui was only forty years old at the time of expiry.

At Talaqan, Genghis sent messages demanding surrender. The inhabitants refused. The ensuing battle was indecisive until Mongol reinforcements arrived from the victorious campaign in Khurasan. Now “they took Talaqan by storm, leaving no living creature therein and destroying fortress and citadel, walls, palaces and houses” (Boyle 1997:132).

At Bamiyan in 1221, the favourite grandson of Genghis was killed during a siege. As a consequence, “every living creature was massacred” (P. Jackson, “Mongols,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

Returning to Mongolia in 1222, Genghis enquired about Islamic doctrine at Bukhara. He approved what he heard, except the Meccan pilgrimage, which he considered superfluous. At Samarkand, he ordered that Islamic public prayers should be conducted in his name, as he had now replaced the Khwarazmshah. The Khan even exempted Muslim leaders (imams and qazis) from taxation (Grousset 1970:244).

Genghis Khan is credited with providing a major boost to international trade. That bounty included the slave traffic. Plunder was an incentive for war. Mongol soldiers looted gold ornaments which they are known to have worn with pride. In relation to the Mongol empire, the nomadic Chagatai Khans remained distanced from urban life. The Khan Baruq (rgd 1266-71) “did not hesitate to order the pillage of Bukhara and Samarkand – his own cities – simply to obtain funds for the raising of an army” (Turnbull 2005:98).

6. Mongol Generals and Christian Crusaders

Depiction of Subutai |

In a distant zone, the Mongol generals Subutai and Jebe attacked West Persia in 1220, leaving widespread ruins. They may have fielded as many as 25,000 soldiers. They sacked the ancient city of Rayy, which never recovered from their attentions. They destroyed Qum, sacred centre of the Shi’ites. They demolished Zanjan, and massacred the population of Qazvin. Hamadan surrendered, the inhabitants being freed from terror by a ransom. A Turkish atabeg (governor) desperately bribed the marauders to spare Tabriz. They moved on to invade Caucasia, where they “cut the Georgian army to pieces near Tiflis” (Grousset 1970:245).

The victorious Mongol generals returned south to Azarbaijan, plundering Maragha. Here they used a favoured Mongol strategy, forcing prisoners to lead the attack and killing these people if they retreated. When Maragha fell, a massacre occurred. The Mongols employed a ruse when departing, to trick those who had escaped into coming back to the city. Then occurred “a whirlwind return of the [Mongol] rear guard, who beheaded them [the survivors]” (ibid). The date was March 1221. Soon after, they returned to Hamadan, where a massacre occurred.

Subutai and Jebe subsequently moved their force back through Caucasia, vanquishing every army, gaining fresh horses, then returning to Central Asia. This expedition involved riding eight thousand miles, “circling the Caspian in one of the greatest cavalry exploits of all time” (Genghis Khan, Lord of the Mongols).

Modern enthusiasm for military history can very easily overlook the agonies endured by victims. A popular name is Subutai, a hero in some internet versions. This general inflicted havoc and widespread death, while living off the land. After causing chaos in Azarbaijan, he ravaged the Georgian countryside, killing many Christians. He destroyed the Georgian army, whom he deceived with a ploy making them believe he was an ally. The Georgians had been planning to join the Fifth Crusade, a topical enthusiasm of the day. Four generations earlier, in 1099, the pious Christian Crusaders massacred the Muslims and Jews at Jerusalem.

The barbarism of the Crusaders shocked even Christians, and the episode would never be entirely forgotten or forgiven by the Muslim states. (Mark Cartwright, “The Capture of Jerusalem 1099,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, 2018)

The gallant Crusaders were “dripping with blood from head to foot” (ibid), according to a later report from William of Tyre. Jerusalem was systematically looted in pursuit of valuables. The pile of heathen corpses was in danger of spreading much feared disease. Muslim prisoners were forced to burn the bodies in huge pyres, after which these assistants were also massacred by the pious and thieving invaders.

The exiled Jalaluddin Mengubirni, the last Khwarazmshah, was nothing of a pacifist. After his defeat in India, he moved to Iran, engaging in much military conflict. His exploits included the pillage of Tiblisi (Tiflis), the capital of Georgia, whose inhabitants he massacred. Mengubirni also fought the Mongols once more, this time at Isfahan, where he inflicted severe losses upon his opponent despite the Mongol victory. He was killed in 1231, possibly at the hands of assassins.

7. Farid al-Din Attar, the Nafs Scenario, and Yazidis

The Sufi-oriented poet Farid al-Din Attar was killed in the massacre at Nishapur in 1221. He was aged 78. Attar wielded the pen, not a sword or axe. He might well have regarded violent events at Nishapur in terms of a tragic contrast with earlier developments, when malamati craftsmen had worked in the ninth century bazaar of that city. No killing or plunder, only honest work and due reflection on the deadly nafs or lower self. Self-conceit, pretension, and hypocrisy were here the enemies. The related ethical code of chivalry (futuwwa) substantially amplified the range of significations in the struggle with nafs. “The core value of futuwwa was altruism and self-sacrifice for one’s social group” (Karamustafa 2007:49).

The nafs scenario is generally uncomprehended or overlooked, nevertheless possessing a capacity of extension into more collective events. The nafs element has a giant profile in world history, where constricting and lop-sided personalities impose schemes of martial conquest, genocide, crime, commercial exploitation, technology overkill, and other potentially harmful pursuits.

The Mongol army was not the only agent of devastation in Central Asia. Centuries later, the Soviet invasion scarred the Afghan landscape with “superior technology” of which Mongol horsemen could not have dreamed. During the 1980s, the Soviet army destroyed Afghan villages and irrigation systems, installed millions of landmines, killed vast numbers of Afghans (up to two million), while abducting and raping Afghan women. The Soviet invasion also aggravated dangerous friction among Muslim opponents, thus producing more terrorism. The ancient Buddhist statues at Bamiyan were destroyed by Taliban zealots in 2001; the task of destruction was delegated to local Shi’ite prisoners who feared death if they did not comply.

The Russia of Vladimir Putin currently has the repute of being a savage country for women, with domestic abuse being notorious. See Russian Domestic Violence (2019).

IS terrorists; Yazidi women protest against IS invasion of Sinjar (courtesy Deccan Chronicle) |

The Islamic State (IS) afflicted the Kurds and Yazidis, becoming internationally detested as molesters in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. In northern Iraq, the IS terrorists massacred Yazidis at their peaceful villages, forcing tens of thousands to flee, while abducting thousands of girls and women into sexual slavery. The fate of women at IS hands is a very strong issue.

The German state of Baden-Wurttemburg undertook a commendable project of salvaging traumatised Yazidi female victims from Iraq. Over a thousand of these victims received deeply needed physical and psychological assistance. Their former captors have been described as sadistic monsters. One report describes how they burned nineteen female Yazidi slaves alive for refusing to have sexual relations. This crime occurred in 2016 at Mosul, where the victims were placed in iron cages. The executions were on view to hundreds of people.

A German doctor heard more than 1,400 "horror stories" firsthand from Yazidi women and girls formerly enslaved in Iraq by IS terrorists. The youngest of these victims was eight years old. "IS sold her eight times during the ten months she was held hostage, and raped her hundreds of times." The horrors of rape and torture caused instances of suicide. To avoid repeated ill treatment, one victim poured gasoline over herself and lit a match. She suffered loss of her nose and ears. She was taken to a hospital in Germany, undergoing more than a dozen operations, even then still needing extensive skin and bone surgery.

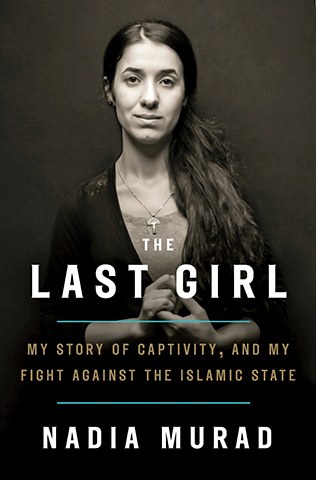

In 2014, Nadia Murad was one of the Yazidi women in Sinjar captured by IS terrorists. She was beaten, tortured, and raped until she escaped to a refugee camp, later moving to Germany. This affliction was shared by over five thousand Yazidi women. Many of these unfortunates could not escape; some are known to have committed suicide. Nadia Murad subsequently gained the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to inform the international community about the devastation of Sinjar. See also When the Weapons fall Silent: Reconciliation in Sinjar after ISIS.

IS (or ISIS) is reported to have displaced, captured, or killed over 400,000 Yazidis. The militant IS also attacked Christians, Mandaeans, Shia Muslims, and Sufis. A large proportion of their victims are stated to have been Muslims. IS killed thousands of Shia Muslims, while also displacing hundreds of thousands of these people. IS are described as extremist Sunni jihad agitators (ISIS Persecution).

8. Hulagu, the Siege of Baghdad, and Mamluks

|

The Mongols conducted their most notorious massacre at the Siege of Baghdad in 1258. This event is told in different modern versions, some with an excised format. A basic detail is that many of the Baghdad inhabitants “and country people who had taken refuge there were put to the sword” (A. Zaryab, “Baghdad ii,” Encyclopaedia Iranica). Others were sold into slavery, a source of revenue.

Hulagu Khan (1218-1265) was the grandson of Genghis. Entering Baghdad after a twelve day siege, he was not feeling sympathetic to the residents, who may have numbered approximately one million. Estimates of the dead vary from 90,000 to hundreds of thousands. Hulagu came with an army of at least 100,000, according to some accounts. The Mongols were supplemented by Turkic and Persian auxiliaries, also 20,000 Christian soldiers from Armenia and Syria.

Hulagu offered the customary (and at times deceptive) opportunity of surrender without bloodshed. The Abbasid Caliph Al-Mustasim declined, sending out a cavalry about 20,000 strong, only to find them annihilated. One version says that the Caliph and his retinue came out of the city, followed by the garrison which laid down their arms. The Mongols killed almost all of them. The Caliph was reputedly rolled in a carpet and trampled by horses. His daughter survived, having no choice in joining a Mongol harem.

A week or more of violence ensued. One section of the population granted exemption by Hulagu were Nestorian Christians (his mother and his favourite wife were both Nestorians). Christians were told to stay in a church for safety. Hulagu’s Christian allies from Georgia were conspicuous in the slaughter of Muslims. A leading general of Hulagu was Kitbuqa Noyan, a Nestorian of the Naiman Turks.

The famed centre of learning known as House of Wisdom was destroyed, along with thirty-six public libraries.

Hundreds of thousands of priceless manuscripts and books were tossed into the river, clogging the arterial waterway with so many texts, according to eyewitnesses, that soldiers could ride on horseback from one side to the other. (The Mongol Sack of Baghdad)

Violence was not new to Baghdad, though not on the same scale as Mongol slaughter. Different zones of the city housed Shia and Sunni religionists, who maintained a quarrel facilitating mobs that frequently resorted to looting, arson, and murder. The Sunni Abbasid Caliph and his officials were viewed by Shi’ites as corrupt and ineffective leaders. The Sunni Caliph had annoyed the Shi’ite contingent with various insults. The vengeful underdogs pledged help to the invaders. Hulagu acknowledged Shi’ite support, even to the extent of posting guards of Mongol horsemen at the shrines of Najaf and Karbala. Many Persian Muslims favoured the Mongols. At Baghdad, the dwellings of eminent Persians were exempt from Mongol pillage, becoming havens of refuge.

Sixteenth century painting of Nasir Al-Din Tusi and his colleagues at Maragha Observatory (British Library) |

Hulagu rewarded Shi’ites who assisted him. One of these was the astronomer Nasir al-Din Tusi (1201-74), living at Baghdad in 1258, soon afterwards persuading Hulagu to build an observatory at Maragha (80 kilometres south of Tabriz). Hulagu obliged by endowing Tusi with an expensive observatory at Maragha, manned by a team excelling in scientific research, with the further advantage of an extensive library and advanced instruments (North 2008:204-209). Maragha was now an astronomer's paradise.

Ibn Kathir reports that only Jews and Christians survived the sack of Baghdad. The Jewish Exilarch welcomed Hulagu into the city. The Jews of Baghdad regarded the Mongols optimistically, because they had suffered at least eighty years of persecution under the Abbasids (Kamola 2013:109).

Hulagu created the Ilkhanate, located in Iran and Iraq. He deputed 3,000 Mongols to rebuild Baghdad, an enterprise only partially undertaken. The Persian historian Juvaini, a secretary to Hulagu, was now appointed governor of Baghdad and Iraq. Born in Khurasan, this benevolent official proved loyal to the Ilkhanid regime founded by Hulagu. He has been criticised for his pro-Mongol stance. Juvaini assisted agriculture by creating new villages and irrigation, and also reducing taxes. He presided over the rebuilding of Baghdad, in a process that saw prosperity return to Iran (G. Lane, “Jovayni, Ala-al-Din,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

During the 1250s, Juvaini composed History of the World Conqueror. “His achievement was to record the events of the Mongol invasions from an Iranian and Islamic perspective” (C. Melville, “Jahangosa-ye Jovayni,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

Hulagu’s cousin Berke Khan, a convert to Islam, was angered by the destruction of Baghdad. This leader of the Golden Horde moved south from Russia to attack. Hulagu countered by going north to Azarbaijan. At Mosul, Arabs and Kurds rebelled. They were besieged by Hulagu, who ordered the ruler to be fatally tied inside a sheepskin and left in the sun, a prey to intolerable heat and vermin. The epilepsy of Hulagu increased; he may have died of a seizure.

In 1260, Hulagu besieged Aleppo, slaughtering the inhabitants of this Syrian city. However, that same year, at the battle of Ain Jalut in Galilee, the Mamluks of Egypt halted the seemingly invincible advance of the Mongols. The Mamluks killed the general Kitbuqa, who had only 10,000 men at the juncture when Hulagu retired his force to Armenia, recognising that his supply line had become exhausted.

Depiction of Sultan Baibars |

The ruler of Egypt was Sultan Qutuz, a former slave. Qutuz originated from Central Asia, possibly from a royal family of Turkic origin (he is associated with Mengubirni). He was one of the thousands of victims sold into slavery by the Mongols. Slave markets existed across the Islamic territories. Qutuz was eventually sold to Aybak, the Sultan of Cairo, where he became a mamluk, meaning the slave class trained as elite soldiers.

Mongol conquest of the Kipchak steppes resulted in many Kipchak slaves. During the 1240s, a substantial number of these people were purchased in Egypt. They became a military class, soon creating the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517). The phenomenon of slave regiments existed from Khwarazm to Egypt, symptomatic of a society in which slavery was pervasive. However, the Mamluk system in Egypt was unique, the regime leaders all being ex-slaves of foreign origin, usually Turkish or Circassian. "Mamluks were purchased from abroad at the age of ten or twelve, were converted to Islam and raised in barracks, where they not only learned military technique but were imbued with loyalty to their masters" (Lapidus 1988:355).

A famous Mamluk name is Baibars (d.1277), a Kipchak Turk (or Cuman) sold into slavery by Bulgarians, later becoming a military commander under Sultan Qutuz of Egypt. Baibars figured prominently at Ain Jalut. After that battle, Qutuz was assassinated. Baibars is strongly implicated; he certainly gained the key role as the new Sultan of Egypt. Acquiring a repute as the ferocious scourge of Crusaders, Sultan Baibars ruthlessly conducted a massacre at Antioch in 1268.

Elsewhere, the Mongols took many slaves to their capital city of Karakorum; these unfortunates were frequently transported to the slave market at Novgorod. Slavery was not unknown in Christian Europe. At the fall of Seville in 1248, the Crusaders took numerous Muslim women as slaves.

Hulagu may have become a Buddhist at the end of his life. When he died, beautiful virgins were sacrificed at his tomb, for the purpose of accompanying him in the afterlife. This was not a Buddhist scenario, instead representing a shamanist custom.

In Iran, the Ilkhanid Khanate, founded by Hulagu, continued under Arghun (rgd 1284-1291). This Mongol ruler may have become a Buddhist. Arghun certainly favoured Buddhism. His final illness “apparently resulted from a life-prolonging drug prescribed by a bakhshi from India” (P. Jackson, “Baksi,” Encyclopaedia Iranica). The quack medicine for immortality was perhaps acquired from the Indian Tantric sector, where such commodities were in vogue. The Turkish word bakhshi derives from the Chinese term po-shih (man of learning). The term referred to a Buddhist lama or scholar, a category who gained influence in Iran during the Ilkhanid era.

Arghun’s son Ghazan Khan (rgd 1295-1304) was reared by bakhshis. However, he converted to Islam at the time of gaining the throne. His capital was Tabriz. Ghazan was converted in the presence of the Kubravi Sufi shaikh and traditionist Sadr al-Din Ibrahim Hammuya (Kamola 2013:175). Hammuya (1246-1322) is associated with the earlier Sufi figure of Najmuddin Kubra (d.1221), active in Khwarazm, and like Attar, a victim of the Mongol invasion.

Kubra became the figurehead of the Kubravi Order. The extent of his actual relation, to varied figures associated with him, is in doubt. For instance, Sad al-Din Hammuya (d.1252) “seems to have stood somewhat apart from the rest of Kubra’s disciples, and to have been shaped as much by a hereditary association with Sufism” (DeWeese 2005:320). Sadr al-Din Ibrahim was the son of Sad al-Din. The father’s association with Kubra, at the very end of the latter’s life, “cannot therefore have lasted very long; little is known of what transpired between him and Kubra” (H. Algar, “Kobrawiya ii. The Order,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

We know of Sufis customarily listed among Kubra’s disciples whose links to him, whether authentic or not, have left few traces even of an association with him, much less of any substantial legacy transmitted from him in terms of doctrine, practice, or communal organisation. (DeWeese 2005:320)

Some disciples of Kubra were never named among his successors in the standard accounts of his Sufi circle. Another factor is rather more disconcerting. “We know of later Sufi lineages that were projected back into Kubra through assertions, found only in relatively late sources, that their founding figures were Kubra’s disciples” (ibid). Caution is clearly required before accepting favoured theories of lineage (silsila). Some reports, about groupings like the Kubraviyya, were shaped not only by Sufi teaching, “but also by the formulation, adaptation, transmission, and manipulation of hagiographical anecdotes, for didactic and celebratory, but also competitive and polemical, purposes” (ibid:321).

Under orthodox Sufi influence, Ghazan destroyed Buddhist monasteries, some of which were converted into mosques. He zealously imposed Islam on the bakhshis. Many of these Buddhists thereafter assumed Muslim identity as a cloak for their own religion. They were apparently permitted to return to their homes in India, Kashmir, and Tibet.

Ghazan Khan and his wife at court, painting from a Mongol manuscript, end of thirteenth century |

On a more positive note, the conversion of Ghazan to Islam facilitated a “reconciliation” between the Turko-Mongol elite and the subject Iranian population. Despite warfare, the economy flourished. Various countries were now in contact more than ever before. Travellers like Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta testify to the prosperity in Iran.

Ghazan suppressed revolts with the “utmost severity” (J. A. Boyle, “Mahmud Ghazan,” Encyclopedia Britannica). His religious bias maintained hostility to the Mamluks of Egypt, themselves Muslims. The issue here was control of Syria.

The bakhshis, or bakhshian, are sometimes linked with the qamans or Mongol shamans. Mongol shamans remained politically influential during the succeeding reign of Oljeitu. However, they were overshadowed by Islam. Like his brother Ghazan, Oljeitu (rgd 1304-1316) was originally a Buddhist before converting to Islam. The bakhshis tried to persuade Oljeitu to abandon Islam. This disappointed party “were most probably shamans rather than lamas” (Jackson, Ency. Iranica, article cited).

Another contingent were shamanist Sufis, represented by Baraq Baba (d. 1307/8), now described as a “crypto-shamanic” Turkmen dervish from Anatolia. Baraq Baba was a disciple of Sari Saltuq, a legendary warrior saint who spread Islam amongst the Turks. Baraq eventually moved to the Ilkhanid court at Tabriz, where he apparently served Oljeitu in diplomatic (or possibly espionage) missions. In 1306 he appeared at Damascus, carrying the Ilkhanid banner. His bizarre appearance caused amusement and aversion. He and his companions wore only a red loincloth, plus a turban to which cow horns were attached.

When Baraq Baba returned to Iran, the province of Gilan rebelled at Ilkhanid rule. Baraq was sent as an emissary to Gilan. He was there killed by Muslims who derided him as “shaikh of the Mongols,” whom they regarded as enemies. Baraq bequeathed a short treatise of enigmatic sayings in Kipchak Turkish. He may have been “an early exponent of the potent mixture of Turkic shamanism, Sufism, and gholat-Shi’ism” that inspired the Safavid dynasty two centuries later (H. Algar, “Baraq Baba,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

Depiction of Rashid al-Din Tabib |

The city of Hamadan harboured a large Jewish community before the Mongols came. Rashid al-Din Fazlullah Hamadani (1247-1318) was a Jewish medic (tabib) who became a Muslim at about the age of twenty or thirty (Krawulsky 2011). He produced the first world history, which he compiled in Tabriz at the request of the Ilkhanid monarch Ghazan Khan.

After the death of the liberal Arghun Khan in 1291, mass violence against Jews occurred. This fact “suggests that Rashid either had converted by that time or else converted out of a sense of self-preservation” (Kamola 2013:116). Rashid gained high rank at the court of Ghazan Khan, a zealous Muslim, whose doctor and confidante he became. Medical practitioners were esteemed at the court.

The near simultaneous death of Qubilai Qa’an [Khan] and conversion of Ghazan Khan have been identified as catalysts of a revaluation among Ilkhanid elites over their place in the Mongol and Middle Eastern cultural worlds. Also, by the time of Ghazan’s conversion to Islam, the Mongols were becoming increasingly acculturated into Perso-Islamic society. All these factors made Perso-Islamic cultural practices, including historical writing, a viable alternative to an increasingly marginalised Mongol tradition. (Kamola 2013:132)

After the death of Ghazan Khan, Rashid became the vizier of Oljeitu (rgd 1304-1316), originally a Christian, subsequently a Buddhist, and eventually a Muslim who adapted to Shi’ism. The Ilkhans, particularly Oljeitu, “distinguished themselves from their Turkish nomadic predecessors, however, by also arrogating supreme religious authority to themselves in the absence of the Caliph” (ibid:131).

Rashid undertook administrative reforms supporting the Iranian population. He acquired much wealth and property in his official role; he was also a philanthropist, building many schools and hospitals with his own funding.

During 1300-1310, Rashid composed the celebrated world history Jami al-Tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles), in response to commissions from both of the rulers he served. Rashid created his own scriptorium at Tabriz, where his Compendium was produced with lavish illustrations and an elegant Persian nastaliq script (Blair 1995). Numerous scribes and artists were involved. This distinctive work covers the Islamic tradition along with the Persians, the Mongols, the Turks, the Jews, the Franks (Christians), the Chinese, and the Indians.

The project was aided by research assistants. The Kashmiri monk Kamalashri contributed to the chapter on the life and teaching of Buddha. The Compendium “is an official history but it is characterised by a matter-of-fact tone and a refreshing absence of sycophantic flattery, even in the sections on Ghazan Khan himself, though the description of his reign is the main goal and purpose” (C. Melville, “Jame al-Tawarik,” Encyclopaedia Iranica).

Legitimation of his patrons was important for Rashid. He included the Turkic legend of Oghuz Khan, meaning a cycle of stories known as Oghuznama. Oghuz Khan was the eponymous ancestor of the Oghuz (or Ghuzz) Turks. The Compendium integrates “the legend of Oghuz into the story of Mongol history and the Ilkhanid cultural project through a vocabulary of administrative and court culture” (Kamola 2013:155).

In his magnum opus, Rashid “is remarkably frank about the shortcomings of early Mongol rule in Persia, but he is seldom overtly judgmental, offering little by way of personal opinion and even less of the moralising tone that was a conspicuous aspect of the work of earlier historians such as Jovayni” (Melville, art. cit.).

The Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani (Blessed History of Ghazan) is celebrated as a dynastic history of the Mongols, while using “significant literary and mythic elements from Turkic, Iranian, and Islamic tradition to cast the Ilkhans within the cultural sphere of the land they ruled” (Kamola 2013:175). Rashid here drew upon books and records, provided by the Mongol elite, to compose his account of the Mongol royal family from ancestors to Ghazan. Rashid is concerned to demonstrate that the Mongol conquest, and the aftermath, amounted to the salvation of Islamic civilisation, not the catastrophic termination by an alien race lamented by other commentators.

The succeeding Sultan was Oljeitu (rgd 1304-1316). Rashid depicts Oljeitu as an enlightened monarch uttering inspired statements. The writings of Rashid “reveal that between 1306 and 1310 Oljeitu learned to perform, and Rashid came to articulate, a new version of kingship less in line with the Kubravi Sufi identity embraced by Ghazan and more heavily influenced by imami (Shia) and emanationist ideas” (Kamola 2013:175).

Rashid encountered problems with powerful rivals at court. A forged letter was used to accuse him of a plan to poison Oljeitu. He proved the document to be spurious. However, soon after the succession of Oljeitu’s son, teenage Abu Sa’id, a rival vizier denounced Rashid, who was now accused of having poisoned the deceased Sultan. Rashid was executed, his estates being plundered.

Only one vizier at this period died a natural death in the web of intrigue. Abu Sa’id Bahadur (rgd 1316-1335) again presided over a prosperous realm. He and his sons nevertheless died of the plague, which caused havoc in the Empire. The cosmopolitan Ilkhanid world now collapsed, splitting into several rival states. After 1335, the Ilkhanid lands “were controlled by innumerable small dynasties of different origins, Mongolian, Turkic, Iranian and Arab” (Manz 1989:11).

11. The Golden Horde and Later Eras

Mongol victory at Battle of the Kalka River in 1223, painting by Pavel Rhyzenko (1970-2014) |

The famed long distance "reconnaissance" expedition of Jebe Noyan and Subutai climaxed with a strong Mongol victory in 1223. At the Kalka River, in Ukraine, they faced a coalition of Rus forces, including Kievan and Cuman. The Rus army may have been no more than 10,000 or 15,000 men, contrary to exaggerated Soviet estimates. The Mongols then returned eastwards to rejoin Genghis Khan.

The third son, and successor of Genghis, was Ogodei Khan (rgd 1229-1241). He granted the status of darqan (protected people) to Buddhists, Taoists, Muslims, and Christians. This did not mean a pacifist rule. In 1236, Ogodei despatched from Mongolia a large army to conquer Russia. The force is reported at 150,000 strong (Rossabi 2009:10). That army was led by Batu Khan (d.1255) and the formidable general Subutai (d.1248). They soon defeated the diverse tribal peoples including Bulghars and Bashkars.

When the Mongol invaders crossed the Volga, the nomadic Kipchak Turks were major targets. In 1238, the Mongol army moved further north and west, looting and burning towns like Ryazan and Moscow. Ryazan was given the option to surrender and pay tribute, but the inhabitants refused, resulting in a battle and slaughter. This proved to be the general pattern, except at Rostov, which escaped destruction after surrender. The inhabitants of Suzdal were captured for use as a human shield. Moscow was little more than a wooden fort, easily burned by the attackers. The disunity of Russian princes was a factor assisting the Mongol victory.

Ruthenians (or Rus) became allies with the Kipchaks, attempting to hold Kiev. The invaders sacked Kiev in 1240, being reported to have slaughtered nearly all the 50,000 inhabitants. The relevant territories became known as Kievan Rus in the nineteenth century. The Kievan society was dominated by Slavic elites, ruling over merchants, peasants, and slaves. Christianity had gained influence in this zone, identified with the nascent Russian Orthodox Church.

The presence of Vikings in this zone was an earlier development. Scandinavian merchants and mercenary soldiers infiltrated East Europe and the Caspian regions; some even reached Baghdad via camel caravans. The early Muslim writer Ahmad ibn Fadlan reports that Rus (Vikings) had strong physiques, blonde hair, prolific body tattoos, and were deficient in ablutions.

Romantic painting The Funeral of a Viking by Sir Frank Dicksee, 1893, courtesy Manchester Art Gallery |

The traveller Ibn Fadlan (877-960) met Rus traders in 922, at a camp of the Bulghars on the upper Volga. The Bulghars were a semi-nomadic, equestrian, and Turkic-speaking shamanist people in the process of conversion to Islam. Ibn Fadlan was an emissary for the Abbasid court. His Arabic work Kitab includes the only known description of a Viking ship burial. Despite some controversy, a number of scholars have specifically identified the Rus as Vikings. The Rus (Rusiyya) encountered by Ibn Fadlan probably came from Kiev. According to one interpretation, the Vikings founded Novgorod to the north and took control of Kiev, becoming known to the Slavs as Rus. The Vikings had been in contact with Islam for more than a century before Ibn Fadlan encountered this mercantile warrior community.

The Kitab describes the funeral of a Rus chieftain, a ship burial involving rape and human sacrifice. Ibn Fadlan considered these people in a negative light, and not merely because of their lax habits in personal hygiene. The Rus indulged in “Viking group sex” with slave girls (Lunde and Stone 2011:xxv). They are described as arriving in boats, accompanied by slave girls whom they traded. “One man will have intercourse with his slave-girl while his companion looks on” (Montgomery 2000:9). The Rus were addicted to alcohol, “which they drink night and day – sometimes one of them dies with the cup still in his hand” (ibid:14). This alcohol surfeit was considered by Vikings to be an ideal death.

“The custom of killing slaves and interring them as grave-goods was not uncommon among the Vikings” (ibid:14 note 46). The ship burial described in the Kitab is very disconcerting to sensitive tastes, despite the romantic and popular elevation of Vikings. Two horses were made to gallop and sweat, and then cut into pieces, their flesh flung onto the ship. A drunken slave girl entered one Viking tent (or hut) after another, being raped by each inmate. Six men eventually committed gang rape with the same girl, in the tent where the dead chieftain lay. The men banged their shields so that her screams could not be heard (ibid:19). She was murdered by two men strangling her with a rope, while an old woman repeatedly stabbed her in the ribs with a dagger (ibid). She supposedly wished to die with her owner. The violent sacrifice resembles a form of slaughter associated with the Viking god Odin. The ship was afterwards set alight.

The Vikings emerge as intemperate and predatory slave traders with a partiality for rape and murderous shamanist rites. The Rus king was apparently modelled upon the Khazar khaqan (Khan), surrounded on his throne by 400 warriors who were sacrificed when he died. The Rus merged with the Slavic population by the eleventh century.

The Kipchak Turks followed a form of shamanism; however, some became Muslims and Christians. Many of them joined the Mongol army, while others fled to Hungary. In the extensive upheavals, many Kipchaks sold their children to slave traders, an influential contingent at that era. The Mongols sold many of their prisoners as slaves; these unfortunates were purchased as mamluks (slaves) in Islamic countries (May 2017,1:221-222). Ironically, numerous mamluks gained a new social status as soldiers.

Waves of desperate refugees moved from Kiev to Moscow. Many churches and monasteries were destroyed. The ferocity and size of the invading Mongol army was shattering. The Mongol expedition created a death toll assessed at possibly half a million people. The Mongols declared that they were sent by Heaven; their victories supposedly proved the claim. “The shock of being conquered by the steppe people would plant the seeds of Russian monasticism” (D. Husseini, Effects of the Mongol Empire in Russia).

In 1241 the same Golden Horde invaded Poland. The mutilation of corpses extended to a terror tactic of severing ears. Moving south to Hungary, more devastation followed. Subudai exercised an iron fist against all resistance. Many were killed or taken prisoner. The invaders would sack a town and leave, afterwards returning to kill survivors who had been hiding in ruins or in nearby forests. Many Hungarians died from starvation.

However, Mongol internal political events then caused a retreat to Russia. The timely death of Ogodei Khan probably saved Europe from conquest. The victorious Mongols nevertheless entrenched themselves in Russia, operating as the “Golden Horde” Khanate. The name Golden is generally attributed to the colour of their tents, one possible meaning. Crimea became the lucrative centre of the Golden Horde slave market, trading with the Ottoman Empire and other Islamic countries.

Reconstructed Sarai Batu, the "movie city" |